Just when you had your surfeit of headlines screaming of blood and gore, come the drumbeats of a new conflict. However, in this new one, the belligerents do not swap bullets but barrels. Yet, this incipient conflict is shaping to be a “mother of all battles” perhaps with a more universal impact than the destruction being wrecked in various corners of the world.

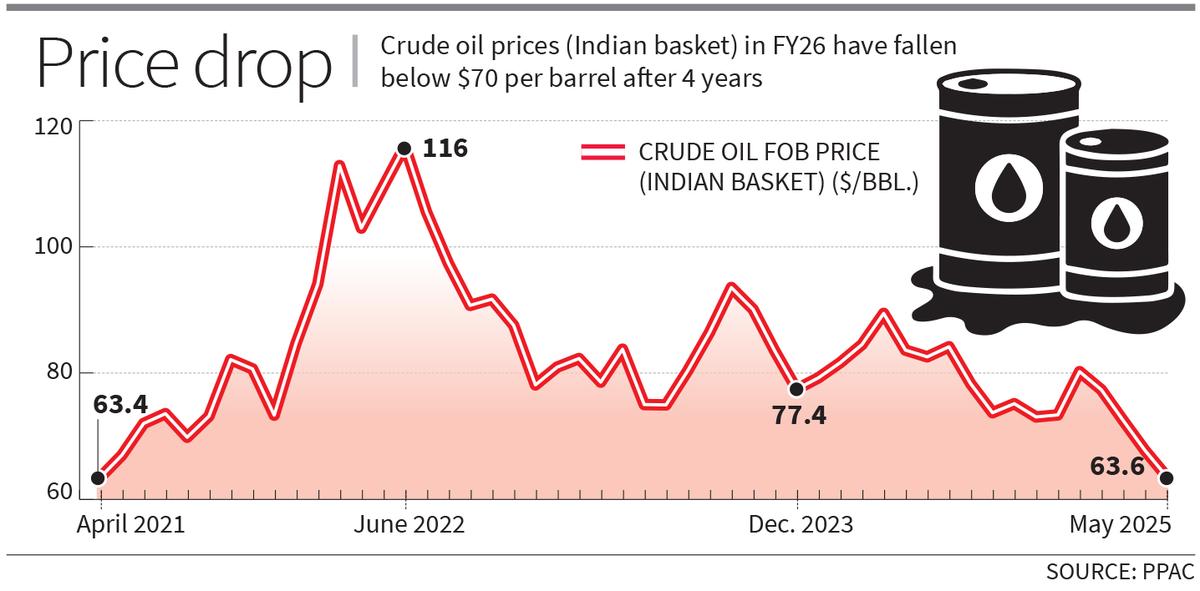

This prognosis may surprise observers who not only missed the weeks of its run-up skirmishes but also the bugle of war, when on May 3, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries Plus (OPEC+) decided to go ahead with a collective output increase of 4,11,000 barrels per day (bpd) from next month (June). This was the third month in a row that the oil cartel decided to raise crude production, cumulatively undoing the 9,60,000 bpd or nearly half of the 2.2 million bpd “voluntary” output cuts eight of its members undertook in 2023, to increase global oil prices in an oversupplied market. There are hints that the full 2.2 million bpd cut would be unwound by October 2025. Though the announced production rise was less than half a per cent of global daily production, the oil market was so jittery that the Brent crude price plummeted by almost 2% to $60.23/barrel, the lowest since the pandemic. It has since recovered to $65/barrel with support from the U.S.-China stopgap trade deal and reports of stalemate in the U.S.-Iran nuclear talks.

Saudi’s strategy

The oil market is still gutted and crude price is nowhere near the triple dollar mark that OPEC+ aimed for. Why, then, has this 23-member producer clique decided to reverse its tactic from reducing supplies to raising production? To find the reasons, we need to deep dive into the oil market of the post-COVID era.

Despite the expectation of a quick turnaround, global post-COVID economic recovery was mostly K-shaped leading to an anaemic growth in oil demand. Meanwhile, oil producers were desperate to ramp up their outputs to make up for lost revenue. It also did not help that several new producers, from the Shale oilers to non-OPEC+ countries, such as Brazil and Guyana, also wanted a piece of the shrunken demand. To square the circle, OPEC+ decided to take a collective production cut of five million bpd, nearly 10% of its total pre-pandemic output. When even this move did not shore up the oil price, a further “voluntary” cut of 2.2 million bpd was taken by eight members. This rope trick also failed to raise oil prices which continued to slide downwards.

While these processes were ongoing, Saudi Arabia, OPEC+’s largest producer, which took nearly three million bpd or 40% of the total production cuts, got increasingly infuriated by endemic OPEC+ overproducers, such as Kazakhstan, Iraq, the UAE and Nigeria. The Kingdom, often called a “swing producer” for its large spare production capacity, prefers stable and moderately high oil prices to ensure a steady oil revenue. However, it has made exceptions in 1985-86, 1998, 2014-16, and 2020 to pursue a market share chasing strategy to punish perceived overproducers. In the past, this market flooding strategy of Saudi enabled Riyadh to eventually impose production discipline among its peers, allowing prices to return to Riyadh’s desired levels.

Now, when repeated pleas failed to stop overproducers, and when Saudi Arabia’s average production fell below nine million bpd in 2024, its lowest level since 2011, Riyadh decided to repeat the playbook: an oil price war in the guise of accelerated restoration of voluntary production cuts.

An oversupplied oil market

However, many observers are less sanguine about the outcome of the Saudi campaign this time owing to several unique and different fundamentals. To begin with, this time the Saudis do not have the usual deep pockets needed to prevail. The oil market is more fragmented with large flocks of freelancing producers. High Capex has been sunk in ultra-deep offshore fields and other difficult geographies which need recovering, even at marginal costs, to avoid adverse political and economic consequences. Moreover, the crude exports by major oil producers such as Russia, Iran and Venezuela are currently hobbled by U.S. economic sanctions which may not last long.

The global oil demand is approaching a plateau and the International Energy Agency (IEA) expects it to grow only by 0.73% in 2025 despite sharply lower prices. The controversial “peak demand” theory does not appear as outlandish now as it did only two years ago when the IEA predicted that global oil consumption would peak before 2030. The signs in that direction are ubiquitous — from the global economic slowdown to the growing popularity of non-internal combustion engine vehicles, particularly in China, the largest oil importer, and growing climate change mitigation. These pessimistic projections are likely to be further compounded by the huge disruption unleashed by U.S. President Trump’s tariff war. The S&P Global agency lowered its global GDP forecasts to 2.2% for 2025 and 2.4% for 2026 — historically weak levels since the 2008-09 recession except for the pandemic period. The World Trade Organization recently predicted a 0.2% annual decline in world trade in 2025 unless other influences intervene. The aforementioned bearish factors can create an inelastic situation causing oil prices to not return to previous levels even after supply-side impetuses are reversed.

All this background begets the question: why has Riyadh picked this moment to unleash the oil war? To some observers, the likely rationale lies in a mix of economic and political factors. To begin with, faced with the inevitable long-term prospects of a buyers’ market for the foreseeable future, Saudi Arabia may be trying to frontload and maximise their oil revenue. They may also be aiming at positioning themselves at the lower end of the oil price spectrum in anticipation of sanctions being removed from Iran, Russia and Venezuela, three of the biggest producers as well as the full rollout of Mr. Trump’s “Drill, Baby, Drill” campaign. Last, but not least, the move was probably intended as a curtain raiser for President Trump’s high-profile state visit to the Kingdom with Al-Saud wishing to be seen as heeding Mr. Trump’s call for lower oil prices to help contain U.S. domestic inflation despite his higher import tariffs hurting consumers. With defence guarantees, a nuclear agreement and over $100 billion in American weapon sales lined up, the Saudis have a lot to gain from the U.S. President’s successful visit.

The impact on India

Although the low-intensity oil war may not hit the headlines the way shooting wars do, it is arguably far more consequential. It is particularly true for India, the world’s third-largest crude importer, which shelled out $137 billion in 2024-25 for crude. India’s crude demand rose by 3.2% or nearly four times the global growth. A U.S. study last year predicted that in 2025, nearly a quarter of global crude consumption growth would come from India. Even further down the line, India’s oil demand is widely expected to be the single largest driver for the commodity till 2040. Consequently, although we may not be a combatant in the oil war, we have high stakes, with a one-dollar decline in oil price yielding an annual saving of roughly $1.5 billion.

While the downward drift of crude prices in the short run due to the ongoing “oil war” may be in our interest, the picture is not entirely linear. Lower oil revenue hurts our economic interests in several ways. It causes a general economic decline of oil exporters which are among our largest economic partners, affecting bilateral trade, project exports, inbound investments and tourism. Lower crude prices also affect the value of our refined petroleum exports, often the largest item in our export basket, and could push down refinery margins. Moreover, the lower unit price of oil and gas reduces our pro rata tax revenues. The Gulf economies sustain over nine million of our expatriates, many of whom may lose their jobs. Their annual remittances, estimated at over $50 billion, may suffer, hurting our balance of payments. Irrespective of the outcome of the ongoing oil war, unless we find a new set of drivers to replace hydrocarbons, the lower synergy may become the “new normal” across the Arabian Sea.

Mahesh Sachdev, retired Indian Ambassador, focusses on the Arab world and oil issues. He is currently president of Eco-Diplomacy and Strategies, New Delhi.

Published – May 20, 2025 08:30 am IST